In the wake of a global pandemic, Dystopian films depicting rampant disease leading to the end of the world take on a new patina of realism. The horror narrative that includes zombies, quarantines, and even the farming of humans for consumption as told through books, movies, and even video games remain timeless and successful.

Despite the extreme presentations of possible futures in films like Outbreak (1995) and Contagion (2011), the reality of COVID-19 showed the very real implications of disease outbreaks. Empty store shelves, lockdowns, and a constant sense of uncertainty and dread were no longer something to experience in a movie theater or in a book alone.

What Are Zoonoses and How Can They Spread?

Disease in horror stories often have one important similarity that often gets ignored: these pandemics and epidemics are zoonotic. Zoonotic diseases or zoonoses are infections that are spread between people and non-human animals. These diseases make up 75% of all emerging infectious diseases and originate in animals used for food, medicine, and clothing.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes zoonotic diseases as a “major public health problem around the world due to our close relationship with animals in agriculture, as companions, and in the natural environment.” Industries like industrial agriculture (factory farming), wildlife trade, and canned hunting. Canned hunting is a type of hunting that involves confining wildlife animals in a fenced area to increase the likelihood of a “successful hunt” for a hunter. Animals are often trapped in the wild and transported to these fenced areas:

- Put animals in stressful, confined, conditions that increase the risk of disease transmission;

- Result in breeding of genetically similar animals which increases the risk of passing a disease quickly between a group;

- Facilitate the close contact between at risk species.

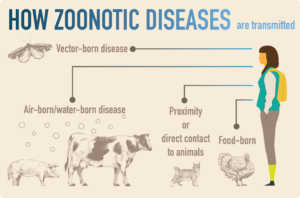

Disease can spread through multiple sources including bites from animals, in the air or water, eating animals, or by just being in proximity to animals. Foodborne and waterborne transmission is from eating or drinking something contaminated, direct contact involves encountering the saliva, blood, urine, etc. of infected animals, and indirect contact involves encountering areas where animals reside or roam. These methods mirror horror narratives. Animal testing, eating animals, and wildlife interaction are the most common disease contraction methods shown in stories.

Disease can spread through multiple sources including bites from animals, in the air or water, eating animals, or by just being in proximity to animals. Foodborne and waterborne transmission is from eating or drinking something contaminated, direct contact involves encountering the saliva, blood, urine, etc. of infected animals, and indirect contact involves encountering areas where animals reside or roam. These methods mirror horror narratives. Animal testing, eating animals, and wildlife interaction are the most common disease contraction methods shown in stories.

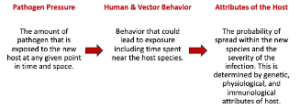

When an infection has moved from an animal source to cause an outbreak in humans that lead to an epidemic, it is often referred to as a “spillover event.” The chances of a spillover event depend on three factors: pathogen pressure, human and vector behavior, and attributes of the host. For example, it is believed that the lack of spillover events of Monkeypox to humans in the Democratic Republic of the Congo can be attributed to the cultural norms that avoid the consumption of certain animals like squirrels.

a “spillover event.” The chances of a spillover event depend on three factors: pathogen pressure, human and vector behavior, and attributes of the host. For example, it is believed that the lack of spillover events of Monkeypox to humans in the Democratic Republic of the Congo can be attributed to the cultural norms that avoid the consumption of certain animals like squirrels.

A key part of a spillover event is that transmission requires close contact between the primary and secondary host species. In this photo, a wet market I covered in plastic as part of social distancing guidelines issued by the WHO, but close contact with dogs, and humans without gloves or other proper clothing to ensure sanitary conditions and multiple types of raw meat products can still be observed.

A key part of a spillover event is that transmission requires close contact between the primary and secondary host species. In this photo, a wet market I covered in plastic as part of social distancing guidelines issued by the WHO, but close contact with dogs, and humans without gloves or other proper clothing to ensure sanitary conditions and multiple types of raw meat products can still be observed.

Specific Diseases

Many infectious diseases you can think of off the top of your head are probably zoonotic including COVID-19 and other Coronaviruses, Ebola, Influenza Type A Viruses, and Rabies. Coronaviruses like COVID-19, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), and Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) are often found in mammals that exist in high population densities or that have strong connections with humans––think bats, rodents, pigs, and dogs. Specifically, since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the disease has been reported in a wide variety of mammals including canine and feline species, mink, and deer.

Like Coronaviruses, Influenza Type A viruses are usually transmitted from animals to humans through direct contact with infected animals or contaminated environments. These viruses include Avian Flu (H5N1, H9N2), Swine Flu (H1N1, H3N2), and other strains specific to a species including horses and dogs. The WHO stated that an Influenza virus with an animal origin has “the capacity to spread sustainably from one person to another, it could start a pandemic because it would be so new that humans would have very little immunity to it.”

You may be aware that an Avian Flu strain (H5N1) ran rampant across the world recently, but what you might not know is that it has already mutated and transferred to mammals like mink being farmed for their fur. Additionally, there are reports of humans being infected with this strain of Avian Flu since the outbreak began. Another point of importance is that the Spanish Flu of 1918 that killed more than 20 million people (about the population of New York) was in fact a strain of Avian Flu.

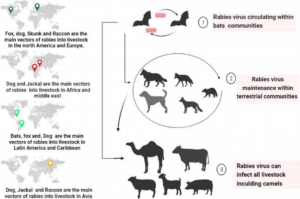

Perhaps, the most widely recognized disease in horror narratives is Rabies. Rabies was the inspiration for many of the infections depicted in stories that fit the zombie, end-of-the-world narrative. Rabies can be found on every continent except Antarctica. Once symptoms appear, the disease is almost always fatal. Terrestrial species including foxes, dogs, and all types of farmed animals sometimes referred to as livestock can catch and transfer rabies.

Perhaps, the most widely recognized disease in horror narratives is Rabies. Rabies was the inspiration for many of the infections depicted in stories that fit the zombie, end-of-the-world narrative. Rabies can be found on every continent except Antarctica. Once symptoms appear, the disease is almost always fatal. Terrestrial species including foxes, dogs, and all types of farmed animals sometimes referred to as livestock can catch and transfer rabies.

Zombies, Vampires, and The Apocalypse

These diseases pose a real threat. Even with our understanding of the origin of Zoonoses and how they develop, our global society does not seem to take note. Society does not necessarily see that horror movies, books, shows, and games seem to reflect our reality more and more. However, we may be able to use horror narratives to our advantage. During the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the movie Contagion (2011) jumped from the 270th most watched Warner Brothers film to the 2nd and was in the top 10 of iTunes rentals for weeks. This shows that people were recognizing the similarities between the reality we were facing in real life and the film narrative.

We can build on that recognition by using other horror stories. 28 Days Later (2002) is a “post-apocalyptic horror film” where the main character wakes up from a coma to find that a highly contagious virus caused a breakdown in society after an infected chimpanzee was released from a laboratory. This film could help kick off discussions on the ethics of animal testing and its role in public health.

We can build on that recognition by using other horror stories. 28 Days Later (2002) is a “post-apocalyptic horror film” where the main character wakes up from a coma to find that a highly contagious virus caused a breakdown in society after an infected chimpanzee was released from a laboratory. This film could help kick off discussions on the ethics of animal testing and its role in public health.

The Flu (2013) is a “disaster film” where a deadly outbreak of H5N1 (the same strain of Avian flu moving across the world right now) becomes airborne. This movie depicts a much-needed change in how industrial agriculture operates in present day.

The Flu (2013) is a “disaster film” where a deadly outbreak of H5N1 (the same strain of Avian flu moving across the world right now) becomes airborne. This movie depicts a much-needed change in how industrial agriculture operates in present day.

There is an astonishing number of depictions of rabies and rabies-like infections depicted in films such as Rabid (1977), Patient Zero (2018), Infection (2019), World War Z (2013), Daybreakers (2009), Cujo (1981 Novel, 1983 Film), and Quarantine (2008). These narratives can be leveraged as conversation starters for how humanity interacts with non-human animals.

The highly successful video game series’ Left4Dead and Resident Evil show different strains of viruses and mutations. Perhaps, the most effective example of a future post-life-changing-zoonotic-disease-outbreak is the book Tender is the Flesh, a novel in which humans must be farmed for food because animals developed a virus that is fatal to humans, by Agustina Bazterrica.

The highly successful video game series’ Left4Dead and Resident Evil show different strains of viruses and mutations. Perhaps, the most effective example of a future post-life-changing-zoonotic-disease-outbreak is the book Tender is the Flesh, a novel in which humans must be farmed for food because animals developed a virus that is fatal to humans, by Agustina Bazterrica.

The reception of Tender is the Flesh is equally as successful as the video games and movies I previously mentioned despite the content of the story. Commentary on the book mentions that it is “a hideous, bold, and unforgettable vision of the future. (i-D magazine, UK) and that it is “a captivating dystopia…” (LA NACIÓN, Argentina). , It paints a terrifying vision of the future. So how do we leverage this narrative to communicate the critical need for changes in policy and clinical research practices?

The Future

The success of this genre and the real fear attached to it has the potential to bring legislative changes to the current system of human exploitation of animals. Some needed changes include:

- A moratorium on factory farms which keeps genetically similar animals in stressful, confined spaces that results in a breeding ground for infection to spread quickly;

- Ending canned hunting like fox and coyote penning that increases wildlife transport across state lines and causes disease like rabies to spread;

- Preventing wet markets because wildlife used for human consumption leads to disease spread and wet markets create a hot zone for transfer between species.

Urgent change is needed because zoonotic diseases are not going anywhere and human exploitation of animals is a major contributor to this persistent threat. The Center for Contemporary Sciences works to unlock the power of science to find solutions that improve the health and wellbeing of humans, animals, and the planet. Join us in preventing the next pandemic.