Few federal laws are considered household names. One of these is the Animal Welfare Act (AWA). The AWA was the first United States federal law to regulate animals used in research. The law was initially called the Laboratory Animal Welfare Act (1966) and was enacted to combat theft of pets to be sold into research. The 1966 law covered the sale, transport, care, and handling of dogs, cats, nonhuman primates, rabbits, hamsters, and guinea pigs and required the identification of dogs and cats. Laboratory facilities and dealers were also required to register.

In 1970, the Laboratory Animal Welfare Act was amended and became what we now know as the AWA. This amendment also specified the coverage of all warm-blooded animals used in research. This may sound good on the surface, but the AWA’s definition of “animal” specifically excludes rats, mice, and birds—the most common species used in labs.

Over the past fifty years, the AWA has been amended five additional times (1976, 1985, 1990, 2002, and 2008). Up until 2002, the AWA did not exclude certain species from being covered, but the new amendment explicitly and permanently denied rats, mice, and birds used in research protections under the AWA. It is important to note that although these species are denied coverage under the AWA, animals used in federally funded research facilities do receive some protections under the Public Health Service Policy (based on the Health Research Extension Act of 1985). These protections only go so far since animals are not used exclusively in federally funded facilities. Experiments conducted by pharmaceutical companies, chemical companies, cosmetic companies, and universities that receive non-federal funds are not covered under the Public Health Service Policy.

Now that we’ve covered a key failure of the AWA, let’s look at what protections are available. For animals who are covered, the AWA intends to minimize the pain and distress of animals in laboratories and ensure “humane care and treatment” by setting minimum standards of care for housing, food, water, veterinary care, sanitation, and handling. In an effort to minimize the pain and distress of animals in labs, the Improved Standards for Laboratory Animals Act passed and amended the AWA in 1985. The amendment included a requirement for research facilities to establish an institutional animal committee that would inspect labs and report deficiencies to the host institution. If the institution did not make corrections, then the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) would intervene. While this sounds great in theory, in practice the care and treatment requirements are poorly regulated and enforced.

The USDA is the enforcement body of the AWA. Despite the USDA being tasked with inspecting labs and monitoring compliance, many violations are not reported or go unnoticed. For example, Neuralink, a company started in 2016 by Elon Musk, has been conducting cruel procedures that potentially violate the AWA, but it was not until public outcry in 2022 that the USDA opened an investigation into potential violations. This lack of enforcement exacerbates the little protections already afforded under the AWA.

Beyond USDA’s poor enforcement, the animal care committees required under the AWA have been shown to be ineffective in protecting animals These committees are known as Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUCs) and were intended to strengthen the standards of care for animals in laboratories. IACUCs are required to have a veterinarian and at least one member not associated with an animal laboratory facility to “provide representation for general community interests” in the care of animals. Despite the inclusion of a community member to represent the interests of animals, animal researchers make the largest number of decisions regarding animal care. Thus there is entrenched bias within these committees that results in little true protection for animals.

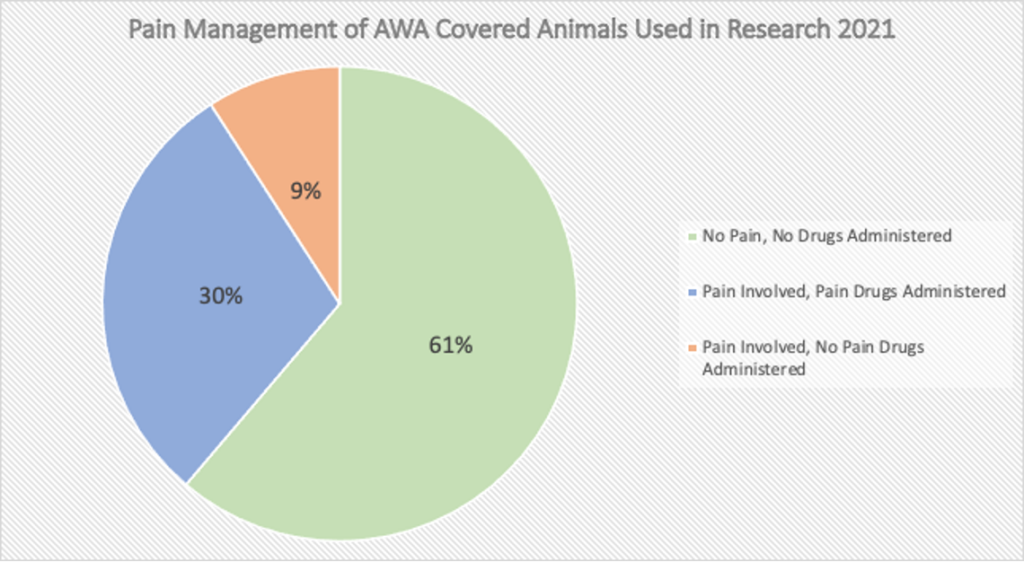

Additionally, and importantly, even for the animals covered under the AWA, the law provides minimal limitations on the degree of pain and suffering an animal may experience. There is a loophole that animals can be denied even the most basic of care if the researchers believe they will interfere with their research results. More than 800,000 animals covered by the AWA (dogs, cats, guinea pigs, hamsters, rabbits, non-human primates, sheep, pigs, and other animals) were reported as used in research in 2021 with nearly 10% being subjected to painful procedures without being given any alleviation for their pain. Thus, animals are routinely starved, denied water, and undergo extremely painful experiments without pain medication or anesthesia.

The AWA fails in protecting millions of animals due to poor enforcement, species exclusions, minimal care requirements, and loopholes for pain and basic care management. So what can we do about it? We should be supporting research methods based on human biology. Human-relevant models like organ chips and organoids better model human biology than animals. Beyond the inherent cruelty of animal experimentation, scientific research increasingly shows that the biological differences between species lead to poor translation to human health outcomes. Join CCS on our mission to facilitate a paradigm shift and move away from animal experimentation.